Active Learning: Optimization != Improvement

Labeled data has become paramount to the success of many business ventures and research projects. But obtaining labeled data remains a costly exercise. Active Learning is a technique that promises to make obtaining labeled data more efficient and has recently been hyped by a number of companies.

At LightTag we provide our customers with a platform to execute and manage large scale annotation projects. Increasing our customers labeling efficencies is literally the reason we go to work. Thus active learning is something we keep hearing about, exploring and experimenting with. But, we keep arriving at the same conclusion, that is the wrong feature for our users and for ourselves as “data practitioners”.

The rest of this post illustrates what active learning is and why we keep deciding not to offer it. In all fairness to AL, the example that follows is somewhat contrived and our conclusion is certainly not a global truth. Still, we think that the principal and risk that this post illustrates occur often in the wild.

Dominating the Papaya market

As a motivating example, imagine you run a papaya stand at the market. Having heard all the hype about AI, you want to build a classifier that tells you if a given papaya is delicious or yucky based on its color (how red it is) and its firmness.

Building such a classifier is easy, you just google “classifier” follow a blog post and you’re off to the races. Except that you need labeled data to train your classifier. And you read on the internet that you need a lot of labeled data.

The problem with getting labeled data is that you need to eat a lot of papayas to get it. This costs time, money and papayas. It may also induce a tummy ache.

Lets look at two scenarios of how you could go about getting labeled papayas, bulk labeling and active learning

Bulk labeling

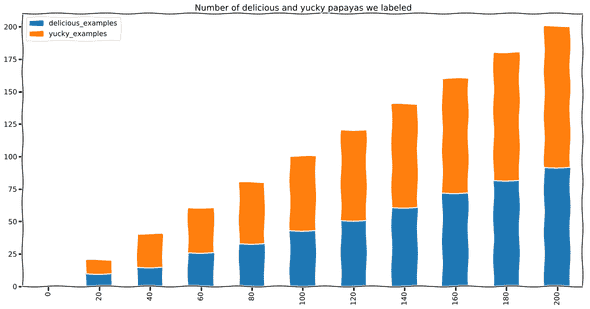

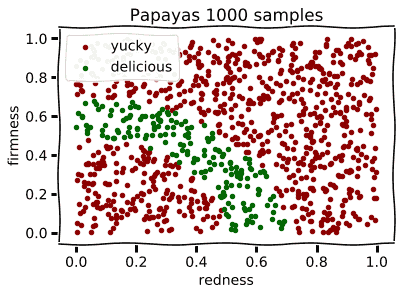

The naive way to go about labeling papayas is to grab a pile of them, and start tasting one by one. Let’s say you have 1000 papayas in your pile, and a few friends to help you. After going through the papayas you’ll end up with a plot like this

Since we’re after a model, lets do a quick experiment and see how a model would perform if we gradually fed it examples. For a model, we’ll choose an SVM with a radial kernel. Such a model can 1) tell us how confident it is about each point and 2) can express a moderately complex hypothesis (the assumption that all of the yucky papayas are in some circular blob)

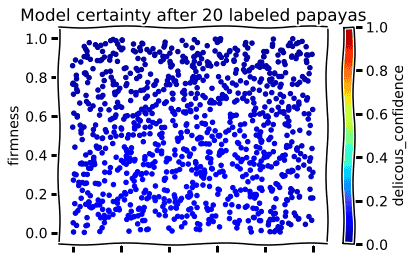

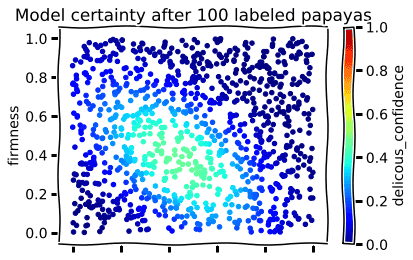

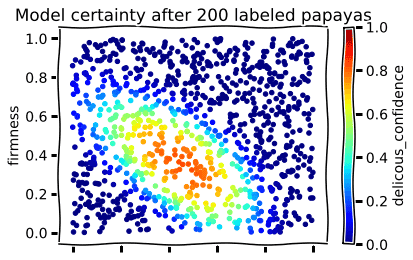

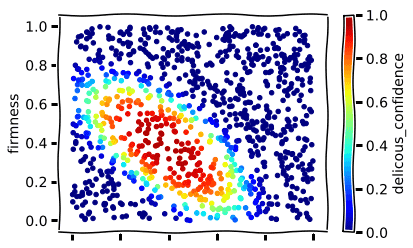

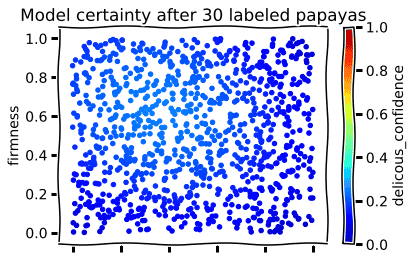

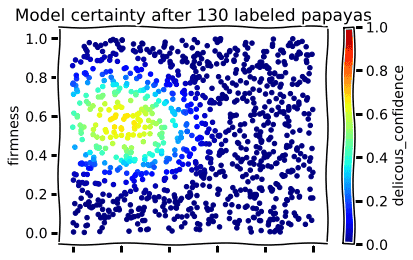

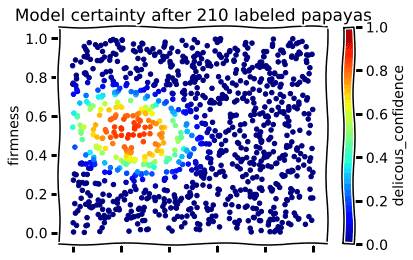

Lets look at how certain our model is after seeing 20,100 and 200 labeled papayas (Red is certainly delicious, blue is certainly yucky and greenish yellow is uncertain)

If we look at how the models confidence evolves as we add labeled data we should stop and ask ourselves, how exactly are we choosing which papaya to taste ?

If we’re taking papayas at random then we’re going to quickly get decreasing returns on our tastings. That’s because as we add examples, the model becomes more and more confident for particular “regions” of the data. That means that showing it more of the same actually teaches it nothing.

Adding Active Learning

This is where active learning comes in. The idea of active learning is to let the model choose what we should label next. To quote Burr Settles, who literally wrote the book on active learning

The key idea behind active learning is that a machine learning algorithm can achieve greater accuracy with fewer training labels if it is allowed to choose the data from which it learns. — Active Learning Literature Survey, Burr Settles

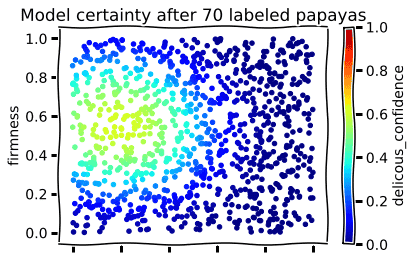

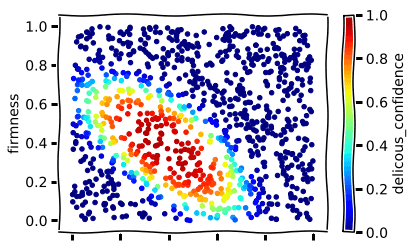

Lets label some papayas with active learning. After each label we’ll retrain the model. At each step we’ll label the example that the model was least certain about (the points that the model thinks “50/50 its yucky or delicious” ).

Then we’ll carry on some more.

So the model seems to have identified a zone that is consistently delicious.

Part Three: Did Active Learning help ?

No.

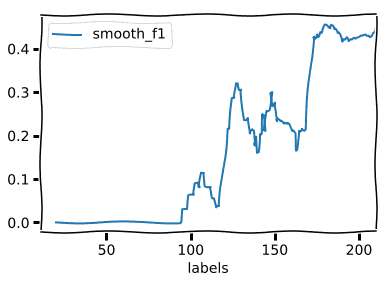

In numbers, the active learning model gave us an F1 score of 0.5 after ~170 labels. Using passive learning we get an F1 score of 0.55 with 100 labels. So no, active learning made us label more and perform worse.

How come?

The reason is a little subtle, and to appreciate its important to remember: using active learning means committing to a model before we have a feel for the data. In turn, that means that if our model can’t understand the data well, than our active learner (which is the model) can’t select data points well.

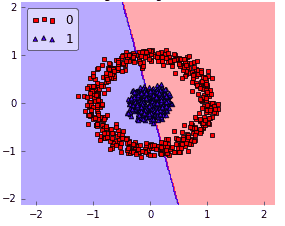

In the case of the papayas, we chose an SVM with RBF kernel (which is the default in scikit learn, and often a good first choice). An SVM with RBF would be really good at finding delicious papayas if they sat on a disk like this

But our papaya data looks like this:

The green delicious class makes a curvy band, not a disk, and so our model is not able to express the boundary between delicious and yucky papayas.

What did the active learner do wrong

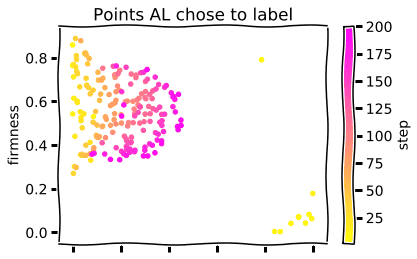

Looking at the points the active learner chose to label at each step is insightful:

We can see that the AL quickly learnt that the right quadrant wasn’t particularly interesting, since everything there was yucky. And so, it did not sample more points from that region.

On the other hand, since the underlying model was not capable of expressing the proper decision boundary, the AL kept sampling points from around (part of) the border between delicious and yucky.

Since the model within the active learner couldn’t express the decision boundary, the sampling the active learner did was biased to the models limitations.

The less significant implication is that we got slightly poorer performance after more labeling.

The more significant implication is that our labeled data is biased to the models limitations, whereas had we sampled uniformly from the data, we would have generated a labeled data set free of bias.

Shooting ourselves in the foot

I say that the biasing of the labeled data set is the more significant implication because it literally goes against the entire reason for using active learning. Hal Daume captured this well in his blog:

The predominant view of active learning is that the goal is a classifier. That data that is labeled is a byproduct that will be thrown away, once the classifier exists.

The problem is that this view flies in the face of the whole point of active learning: that labeling is expensive. If labeling is so expensive, we should be able to reuse this data so that the cost is amortized. — Hal Daume in the Natural Language Processing Blog

But if our labeled data is biased to a model we can’t use it effectively again, we lose most of our ability to amortize the cost. If we were to accept this data as a golden truth and test another model on it, we may incorrectly penalize the new model. If were to be disapointed with our current model, and train a new one on the same data — our new model would have the same biases as the old one, regardless of how expressive it was.

At LightTag we want to make our customers labeling work more efficient. While the promise of active learning seems very much in line with that, the potential for corrupting our customers data set is very much out of line. That is why we don’t offer active learning.

Conclusion

We set out to label data in the most cost effective manner we could. Active learning promises to make our labeling more efficient by letting our model select what to label. Instead of sampling randomly and labeling redundant examples, active learning lets the model choose what to label next, based on what will be the most informative.

But, by letting the model select what to label, we bias our labeling efforts towards the limitations of the model, and these limitations are not necessarily congruent with the reality of the data. This essentially reduces the efficiency of our labeling process and becomes a drain on our labeling resources.

As labeled data becomes a more significant part of our data strategy, and as models themselves become somewhat commodity, its important to ask ourselves if active learning really serves the goal we are looking for.

I’m reminded of a beloved passage from the book The Goal. In the book, Alex Rogo is a struggling manager of a manufacturing plant who meets his old physics teacher turned factory expert ,Jonah. Alex begins telling Jonah about how robots have improved the factory and the following conversation ensues:

Alex — “Robots increased productivity by 36% in one department”

Jonah — “Are plant inventories down?” : No

“Is employee expense less?” : No

“Shipping more product?”: No

Alex — “But we must keep robots running to maintain efficiencies”.

Jonah — Then “Inventories must be sky high and orders must be late.”

The lesson I’m alluding to is that just because robots (or active learning) make a process more automated doesn’t mean they’ve served the goal. They might be cool, they might be cutting edge, but it is our job as practitioners to make sure they are doing what we are trying to do and not only please us intellectually.

Technical addendum

Active Learning is a broad and well established field but to keep this post within a decent length we didn't cover all of it. For the inquistive reader, we suggest you take a look at Active Learning Literature Survey, Burr Settles.

Query by committee

Importantly, the active learning method we presented above is the most naive form of what is called "uncertainty sampling" where we chose to sample based on how uncertain our model was. An alternative approach, called Query by Committee, maintains a collection of models (the committee) and selecting the most "controversial" data point to label next, that is one where the models disagreed on. Using such a committee may allow us to overcome the restricted hypothesis a single model can express, though at the onset of a task we still have no way of knowing what hypothesis we should be using.

In either case (QBC or US) it's our (the data scientists) job to anticipate these problems and adjust for them. A sampling algorithm that mixes the uncertainty/controversialness with some mechanism to improve overall sample representativness can improve performance.

Search instead of Label

In some ways active learning is a way to let the model ask the labeler for feedback. This concept can be extended to allowing the labeler to introduce their knoweledge into either the model or the data. In Why Label when you can Search Attenberg and Provost argue this point convcingly, espeacially in the case of highly imbalanced data. Their premise is that the labeler knows what the is being searched for, and that knoweledge can be used to quickly get to the most relevant examples.

In Closing the Loop: Fast, Interactive Semi-Supervised Annotation With Queries on Features and Instances Settles introduces Dualist a system that mixes Active Learning, semi supervised learning and "feature labeling". Feature Labeling extends active learning by having the "model ask about a particular feature". See the demo here.